Thinking about AI and empowerment

Co-Founder of LinkedIn Reid Hoffman's opinion piece about AI empowering humans was published by the New York Times this morning. In the piece, Hoffman writes reductively about “tech skeptics” and their haphazard use of the word “Orwellian”, implying an overstating of the harms of various “technological innovations”. He writes, “what I’ve found through my own experiences is that sharing more information in more contexts can also improve people’s lives” and “I believe A.I. is on a path not just to continue this trend of individual empowerment but also to dramatically enhance it”. The examples he uses of empowerment include Joe Rogans one-man podcast "empire" and an assumption that presidents aspire to be social media influencers.

Subsequently, he describes how the digital tracking of behaviors and activities can and should eventually and significantly drive our decision-making processes, from the complex to the more mundane. He states, “When you’re trying to decide if it’s time to move to a new city, your A.I. will help you understand how your feelings about home have evolved through thousands of small moments…” and “your A.I. could develop an informed hypothesis based on a detailed record of your status updates, invites, DMs, and other potentially enduring ephemera that we’re often barely aware of as we create them”.

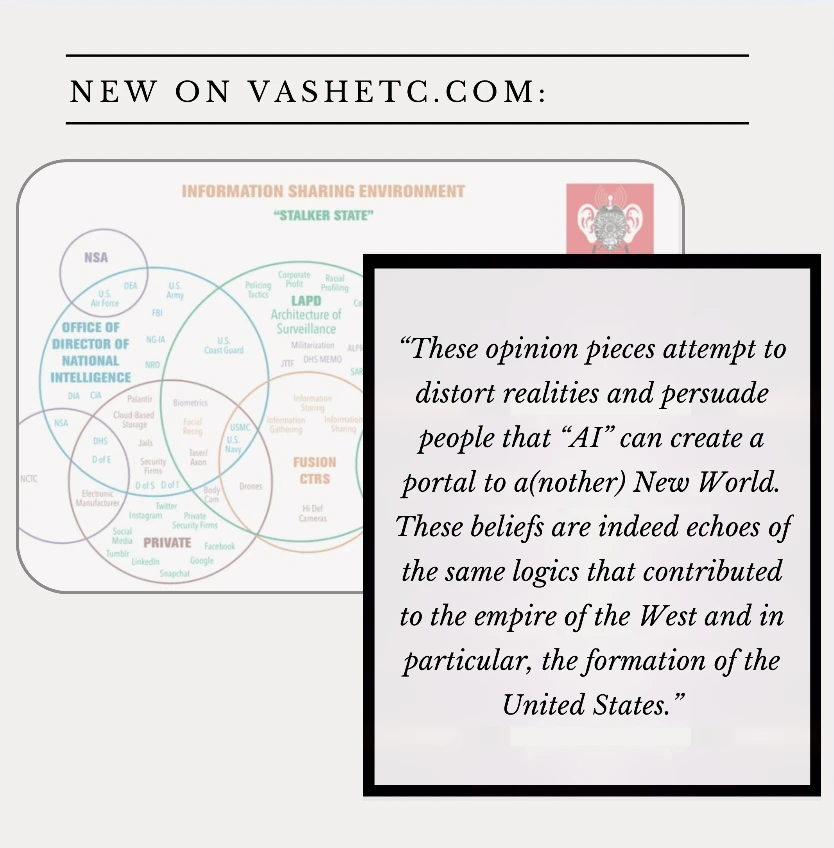

Whenever these opinion pieces from big tech stakeholders come out the (many very real) risks to individual and community health, privacy, autonomy, and freedom are watered down to what can be understood as a seemingly annoying impediment on technological progress, or worse, erroneously portrayed as a wide sweeping opposition to all technological innovations without adding any context into the sociopolitical conditions in which people exist. What is conveniently missing from these opinion pieces is any real engagement with the concerns people have regarding the resources (water, land, energy) required to make “AI” happen, and the labor. These opinion pieces attempt to distort realities and persuade people that “AI” can create a portal to a(nother) New World (evidenced by his statement that “those who choose to pursue this new reality”’). This is something discussed by researchers Timnit Gebru and Émile P Torres. These beliefs are indeed echoes of the same logics that contributed to the empire of the West and in particular, the formation of the United States.

In fact we see versions of these types of arguments for “AI” in many different areas of work. Though in my area of work algorithmic and “AI” driven decision-making processes are not described as part of a “new reality”, they are touted as a fix to a variety of socioeconomic, labor, and sometimes “equity” issues. These fixes include less caseworker burnout (increasing productivity of laborers), more efficient service provision (reducing the "waste" or "theft" of "scarce" resource), reduction of human bias (implying the decision making can be unbiased), and ability to predict “crime” before it happens (in efforts to uphold the social order). However, each of these touted “uses” are often overstated and muddled with or in already harmful systems and processes. It is not a good idea to make bad things work more efficiently, and it is a bad idea to pretend that some tech-mediated utopia awaits us.

These reductive take that aim to oversimplify and mischaracterize critiques of “AI”, various surveillance technologies, and companies like “Open AI” are intentional and divisive, and unfortunately will be growing in years to come. Whereas Hoffmans (et. al) imagination dreams up a world in which we can and should opt-in to ‘AI” (which he describes as something that will augment and “improve” his already likely surveillance-free life via improved data collection), many people I work and organize with dream of freedom, much of which includes fighting to escape the cycles of entrenchment that mass data collection often guarantees. This includes being victim of incorrect automated benefits determinations that revoke medical coverage, generational family separations that rely on “proxies” of maltreatment and predictive risk assessment tools, incarceration and criminal charges based on facial recognition technology, geolocation tracking that upends user privacy and breaches reproductive rights, and genocide aided by OpenAI and other technologies of destruction. These are not fantasies or fiction that critics made up based on a flimsy reading of Orwell. The harms I listed are very real harms that impact peoples day to day lives. Really, they impact everyone’s day to day lives due to the climate and labor implications alone. In this piece, Hoffman asks the audience "do you feel seen?" by ChatGPT. I amend this question to call to attention a deeper question, who is being "seen", who is "watching", and why?

Our critiques have never been just about how technology can replace human labor, but rather how technologies and the data it requires or creates restructures the sociopolitical, geospatial, and economic conditions in which we exist. These technologies have a very real impact on who is able to retain true autonomy, freedom, and well-being — and who is doomed to be stuck in cycles of extractive and organized abandonment. In 2025 some of us will continue to speak out and boldly against these mischaracterizations of our critiques, and these fantastical visions for our shared future. True empowerment comes from collectively dreaming with our communities in a way that disrupts the imaginations of those who do not have our best interest at heart, those who wish to capitalize off of our suffering in the name of innovation. It is essential that we dare to remember this in the coming years.

If you enjoyed reading this please consider subscribing to a membership to help pay for medical expenses