Part I: “I shall enjoy the fruits of my labor, if I get freed today”

It has only been two days since the Super Bowl performance and I am still reeling from the radiance of SZA and Serena, the eloquent dragging of Aubrey, and the simple genius of Kendrick’s 13 minute set. This reflection is a first impression stream of consciousness and not neat and tidy, so bare with me. Regardless, writing this has been a pleasure. Kendricks performances have always been memorable. The first time I saw him perform live was in 2015 from the press pit. My hands couldn’t stop shaking as I tried holding my camera steady to get at least one good picture. Mid set he dropped a bunch of red and blue balls on the crowd as the lyrics “if Pirus and Crips all got along…” blared through the festival grounds. I'm grateful that we are still able to experience his music, art, and mind ten years later.

I’m going to get into my thoughts of the performance, but first let me get this off my chest. As someone very critical of, well everything, engaging with the Super Bowl and the NFL was and is riddled with tensions for me. With the pandemics, the state of democracy right now, genocides, and state sanctioned abandonment across Louisiana, I can’t help but feel disdain for so many parts of the event. Simultaneously, I cannot ignore how much joy I experienced getting to watch and engage with the audacity of Kendrick Lamar, my favorite rapper since I was 17 and first heard “Faith” in 2009. Most times I don’t know how to discuss these intricacies and contradictions, and I have been recognizing that I regularly feel these tensions in my day-to-day whether it’s working jobs that profit the elite or during my futile attempts to try and chip away at my grief and anxiety with inadequate resources. Somehow, I (we) still find ways to experience and create joy through it all. And I think that’s remarkable. This is not an excusal. In this part one of my stream of consciousness, I’m validating how difficult it is to feel this tension, and how feeling it has influenced how I viewed the performance as well. In this piece, I’m acknowledging the inspiration and joy Kendrick’s creativity has brought me over the years while also grappling with the landscape in which we create and enjoy Black art.

The Super Bowl halftime show was packed with meaning. I can’t speak on everything because there’s too much to cover. I won't even get into the significance of having Samuel L Jackson as Uncle Sam, SZAs performance, Serena getting her lick back via glorious crip walk, or the Gloria jacket. The performance was a 10/10 no notes. As for the rap beef, Drake is down bad. Period. But as I sat with the performance over the past two days I recognized a few themes, one of which is control. Of course this is likely obvious upon first watch or listen.

As many have recounted over the past few days, Kendrick loops us into a story about the “Great American Game” straightaway through Black Uncle Sam’s opening dialogue. My first thought was that the performance and the slogan were alluding to the government and music industries oppressive attempts to control Black people, attempting to mold them into a palatable extractable entity — a thing created for consumption, labor, and entertainment. Of course this is rooted in the echoes of the transatlantic slave trade, much of what many of us already know and much of which K Dot has explored in his previous projects. This perspective was made more evident by the continuous cut scenes of Uncle Sam instructing us to tighten up, stay calm and peaceful, and refrain from being too “ghetto” (aka refrain from the tropes associated with Blackness in America). Peaceful protest anyone?

The stage consisted of a simple but thoughtful set up that utilized the entire stadium. The main performance stage was laid out as a controller, accompanied by a street running through what would be the middle of the buttons. The street was wide and surrounded by streetlights and surveillance cameras lining either side. Part of the stage expanded to the crowd with lighting being manipulated throughout the set to show different signs in accordance with the game stage, words including “start here”, “warning wrong way”, and “game over” flashed at different parts of the show. My visibility, however, was entirely based on the Apple Music version of the performance which was shot by a few cameramen on the stage itself and a camera from birds eye view.

After watching the recordings from people at the stadium, I recognized that there were multiple different ways to engage with the performance based on vantage point, some of which were inaccessible to people only watching through the cameras lens. Kendrick masterfully controlled the reception of his storytelling by utilizing various camera angles and lighting sequences, while also playing with movement and set architecture. These manipulations impacted the audiences vantage points in real time and could completely alter the meaning and interpretation of the performance based on how you viewed it. This realization made me feel like I was in a simulation, a game indeed, and I have been grinning from ear to ear ever since.

But let’s back up, first impressions right? Kendrick opened the show by rapping an unreleased track on top of a GNX. I hate to toot my own horn but in our pre show estimations I definitely hoped this would happen. I’m not about to get too into the GNX discourse because I’m not a car girlie but I will say that my very cursory look into K Dots beloved car shows that it was thee car at the time of its conception. I am sure K Dot and a bunch of Black kids during the 80’s dreamed of racing this so called “Darth Vader” joint — (“Ain’t no other rap king, they siblings. Nothing but my children, one shot they disappearin’, I-am-your-father type vibe). Performance wise, the GNX was comparable to the Ferrari F40 at the time and only 547 were made. I love the notorious reputation of the GNX which is exemplified in this very 80’s commercial, enticing the consumer to join the dark side as Bad to the Bone plays in the background.

Real g shit, what an opener. But what almost made me cry was when all of the dancers started popping out that mug.

My first impression was awe. It was a reminder that Kendrick constantly puts LA and other Black creatives on. When he eats, others eat too. I thought about how exciting it must have felt for the performers. It also made me proud. Sometimes you really do gotta pop out and show ninjas. Talk your shit Kenny! But upon more consideration, I started thinking about the pressure that’s placed on Black men as mentors, fathers, brothers, husbands, artists, and educators everywhere. Their lives are consistently under a microscope, or surveillance camera. Kendrick Lamar has alluded to this over the years.

My first impression was awe. It was a reminder that Kendrick constantly puts LA and other Black creatives on. When he eats, others eat too. I thought about how exciting it must have felt for the performers. It also made me proud. Sometimes you really do gotta pop out and show ninjas. Talk your shit Kenny! But upon more consideration, I started thinking about the pressure that’s placed on Black men as mentors, fathers, brothers, husbands, artists, and educators everywhere. Their lives are consistently under a microscope, or surveillance camera. Kendrick Lamar has alluded to this over the years.

The introspection and creativity Kendrick has shown us over time through his music started to become more evident to me very early on in the performance. People hopping out the GNX was love, but was it also part of the game? I started falling down a mental spiral of questions. Can you stay genuine to your roots while amassing capital? How do you put people on without selling them and yourself out? What do you do with immense influence and responsibility as a Black man, especially one tangled up in the industry?

The introspection and creativity Kendrick has shown us over time through his music started to become more evident to me very early on in the performance. People hopping out the GNX was love, but was it also part of the game? I started falling down a mental spiral of questions. Can you stay genuine to your roots while amassing capital? How do you put people on without selling them and yourself out? What do you do with immense influence and responsibility as a Black man, especially one tangled up in the industry?

Not only that but what happens when we come together and things pop off? How do we handle our beef under the constant gaze of the oppressor/controller? Do we run to the courts (uh say Drake), do we kill each other, do we lock each other up? I think back to conversations I had while organizing with my Skid Row comrades, talking about how the prevalence of police and the criminal legal system reduces our communal imagination and our ability to handle conflict without relying on forms of policing. As one might say, it’s deeper than rap.

There was a simultaneity of narratives happening with this performance. I remember one time my professor lectured our grad seminar on legibility because we were frustrated reading through some dense text. Someone said “it’s just not legible”. Our professor took the time to teach us about legibility and how it didn’t always mean what we thought it did. Sometimes when you read or engage with Black text or art a specific meaning will only be decipherable if you can connect with it based on a common experience. Some text and art is more easily deciphered and given meaning when engaged with as a group, as black study. It’s rigorous, and sometimes it’s difficult and painful, but it turns illegibility on its head. And legibility is not always synonymous with accessibility. I love that Kendrick talks about this in Not Like Us and his teaser track. When Kendrick’s raps “You would not get the picture if I had to sit you for hours in front of the Louvre” in the opener, he meant that shit. I appreciate him for the level of entertainment he planned for the Super Bowl, but also for the discussion he laid out for us underneath, around, and within the performance.

Kendrick can be serious, goofy, a straight shooter, a g, but hands down he is always a creative genius. Over the years people have been saying Kendrick can’t put out a hit song. (Which has always been cap, but I digress). To play on these critiques he released bops like Not Like Us and tv off, “give them what they asked for”. In doing so, he showed us the role WE, as the enjoyers and engagers of the art, play in controlling what is and isn’t taken up by artists and the industry heads who run the labels (eyes on you Lucy). In many ways we playing right into the game. We do it through our hot takes, our opinion pieces, our need and desire for drama, and our general consumption of art without true engagement and respect for Black artists as human. I am particularly thinking about dehumanizing situations like Meg the Stallions experience.

We are not just mindless consuming machines here to be entertained, we play in active role in all of this, for better or worse. He’s calling Drake a whole ass pedophile, but how many of us will still include him in our playlists? And what if all of us just chose not to? It truly begs the question of who is really in control and how we can and do use our power. I can’t help but feel like Dot is asking us to sit with these questions.

This is where I started to really get into my head with the performance. When I first heard Dot say the revolution WILL be televised it made me pause, it was not what I expected. While everyone is hyping this part up as an “I’m that ninja” moment, I have been thinking about it in terms of gaze and the overall theme of control.

I am jumping around but stay with me.

I want to specifically talk about my first impressions of “peekaboo” and “Not Like Us”/“tv off” as it relates to this. First, when Kendrick performed “peekaboo” I was shook. It’s also when I realized that so much of his performance was to or for the camera, and not necessarily the stadium audience. He was making sure he was almost always in frame directly addressing the camera audience. That’s part of the game right? That’s what we wanted right? During "peekaboo" Kendrick was within the X, the only stage with walls in which those in the stadium attendees could not clearly see unless seated with a birds eye view, or directly looking at the screens showing the camera footage. He further controlled the camera shots by moving his body around, comically popping up on the first peekaboo (he’s a diabolical troll fam). And it was up. I was hyped.

This segment of the performance had me thinking about a concept I’ve discussed in previous posts (and my dissertation) called dark sousveillance created by Simone Browne in Dark Matters) which she describes as “a way to situate the tactics employed to render one's self out of sight, and strategies used in the flight to freedom from slavery as necessarily ones of undersight”. She goes on to say, "Dark sousveillance, then, plots imaginaries that are oppositional and that are hopeful for another way of being. Dark sousveillance is a site of critique, as it speaks to black epistemologies of contending with anti black surveillance”, and that it “…charts possibilities and coordinates modes of responding to, challenging, and confronting a surveillance that was almost all-encompassing…”.

Kendrick crafted the stage architecture in a way that allowed for pockets of invisibility/hypervisibility based on different audience vantage points. Kendrick's set was a contestation of the attempted censorship that stemmed from the lawsuit, a dismissal of the legal and industry eyes that were on him, and a declaration of subversive artistry and joy. I love how this ties into Simone Brownes concept of dark sousveillance, but also her work in general in that she calls us to question who is being watched, who is watching, and in what capacity—particularly as it pertains to Black people. I had this in mind as I scanned the stage.

There were performers seated on the street lights as an ode to the city life, but were they ops? Were they guardians? Homies? Scorekeepers? Spectators? This play on gaze seeped throughout the entire set. Although stadium-goers were able to see the dancers in black who were in the periphery or margins of the stage, particularly those gathered around the street section of the stage who were holding the pg lang flags (site of the protest), they could not clearly see Kendrick and the performers while inside of the X during peekaboo unless they watched the tv screen.

In contrast those watching through the camera/tv only could only see what he and the camera man wanted us to see and when. We missed the peripheral details, the elusive performers in black weren't apparent until the end performance of “Not Like Us” (the final level before game over) when he chose to have the house lights on during A Minoooooor. *Revelation*. Exposed.

Sometimes our joy is not for their gaze. Sometimes we scheme in the shadows. Although tv viewers at home got to consume (in detail) Dots entire performance without much “distraction”, we missed other critical details like the directions and warnings portrayed from within the crowd. At times, we were lost because the camera was not focused on those other details. Funny how that works. I loved this play on gaze. We see what we want to see. We see what he wanted us to see. It was all crafted knowing it would be consumed in this way. We are part of the game.

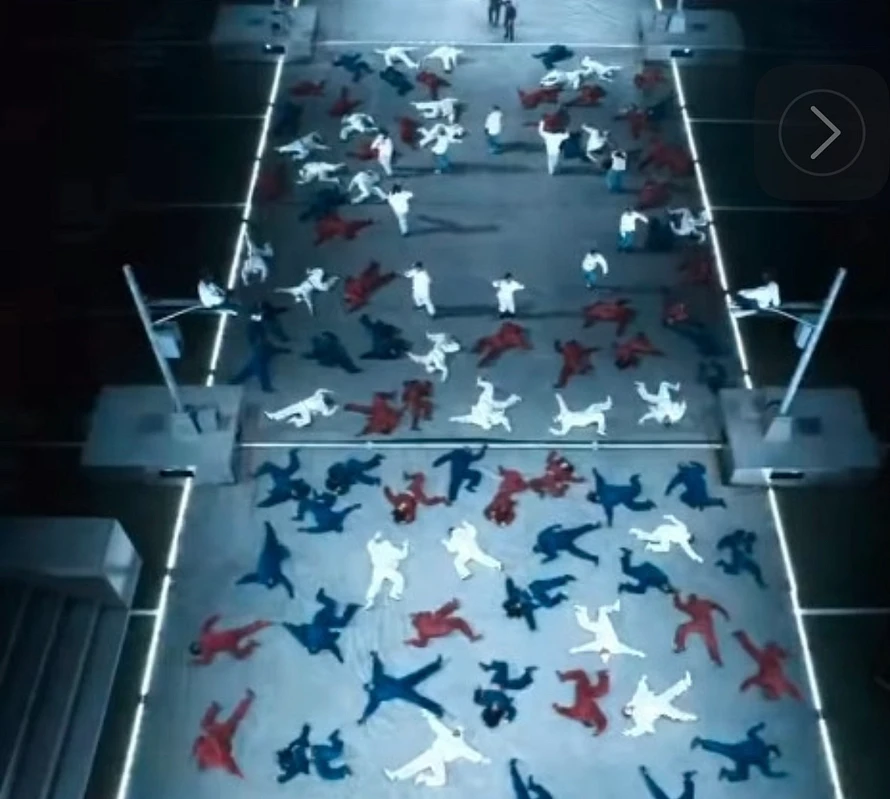

There’s one part of the performance that made me gasp, and it was the pause after the John Stockton bar in “Not Like Us”. The performers were laid out in an eerie resemblance to the forensic investigation crime scene chalk symbols used on the streets when there’s a murder.

It was so quick you could easily miss it. This was the best visual of the night to me. I’m still deciphering what the circle of standing performers means, but having everyone laid out like this initially made me think of Kendrick’s "Rigamorotus" video. “Don’t ask for your favorite rapper, he dead”!

However, when I started to sit with it more I thought about the spectacle, performance, and reality of mass Black death. It’s not lost on me that New Orleans has seen devastation, not only through the slave trade but also notably during and after Katrina when masses of Black people were forced to exist in horrendous conditions, particularly within the Superdome. These suffering bodies were “dead” to some of you, some of them. Waste, thing, to be used or otherwise forgotten.

It made me think about the bloods and crips in the streets of LA (reminding me of having to remove our blue shoe laces when we visited my aunties house on menlo as a kid) and how the death and destruction of Black communities is recycled, taken and used to propel the prison industrial complex, the music industry, and everything in between. We are the creators, the consumers, and the consumed. Whose holding the controller? They need us laid out in the streets as much as they need us to live so that they can keep taking — an almost guaranteed cycle of destruction. They find new ways to profit off of our suffering and I have been thinking about the ways the Super Bowl performance aides in or resisted that.

The performers laid out on the street was a statement for us, but also for those wealthy folks in the stadium watching an NFL game (NFL with majority white owners) in a city and country still devastated by ongoing disaster. A stage-street filled with a momentary fleeting spectacle of Black death, what and who was it for? K Dot gave us what we asked for, are we satisfied? I am still stuck on this and am reminded of Christina Sharpe’s words from In the Wake:

Respectability. Representation. Revolution via Apple Music? Although “Not Like Us”/“tv off” felt like a victory lap (we reached the final level of the game!), especially when the performers started leaking onto the green outside of the bounds of the stage-street, I had to think, did we really win? Of course on the first watch I was purely hyped. The questioning came the next day like a lingering bitter aftertaste. Is it victory having Black people in high places if they’re abiding by, allowing for, and exacerbating the conditions that lead to our premature death and destruction (when we're the ones holding the controller)? Do we win by having a Black Uncle Sam? Does anyone win this game? Do we even have a choice in whether or not we play? Why did it bring me so much joy though?

I throughly enjoyed this performance. But after thinking about it I was like dang, am I even supposed to enjoy it? (Yes and no). It is deep. I feel like Kendrick called me out/in, particularly when it comes to how I consume art, violence, tragedy, beef, and music. I have so many emotions. I feel immense joy and appreciation from the art. I have been so depressed lately and I genuinely needed this inspiration. I laughed hard at how hard Drake was dragged. I feel awe over the audacity to bring this conversation to a global audience as a Black man during this political climate. I feel tension in watching for entertainment. I feel enraged that I’m a pawn, an npc, and at the same time partially controlling the game. One thing I know for sure is that Kendrick always reminds me how important it is to not wait for our oppressor’s to call the shots. We are not just spectators. We never were. We have to find a way to free ourselves, and to enjoy ourselves in the midst of the struggle. It will be mucky, full of failures and experiments, riddled with tension, but we are worth it.

A little about me.

(This section is not pertinent to the review above so feel free to skip!)

My dads dream was always to have a radio station. He frequently made me record voice overs for him and listen to his mixes back on tape. He would play them in his red bmw with the bass so loud that it rattled my entire body. All of my dads spare time was mostly spent listening to music or creating music mixes. This love for music has been passed down to me and my brothers, and we have shared this passion with our closest friends growing up. Growing up in North Las Vegas was... an experience. We were consistently ranked as the second worst school district in the country. There were multiple shootings at school and the police regularly pepper sprayed us and did searches of our bags during class time. There was little for us to do in Vegas, it was a city tailored to adult tourism. No one poured into the youth, into us. Disinvestment from the city and county was felt by our corner of the valley specifically.

Growing up in the North we had to observe and experience a lot of state violence and I believe this impacted our perceptions of ourselves. Compounding all of this, the recession (and my dads retirement from the army) made things very conflict-ridden at home. For years I really didn’t know anything else. It was the norm for us. Through the long dry and scorching summers, crusty textbooks and defunded after school programs, we all found sanctuary in the music.

It was game over when my brother bought FL Studio for the first time. Friends would frequently come over to record in our makeshift recording studios (aka a mic and pop filter in my tiny little bedroom). All of us spent long afternoons and endless nights surrounding ourselves with music whether it was making beats, testing them out in the van, recording raps, shooting videos, or going to local shows. It really did deter us from messing around in the streets. I’m not sure if my mom realizes we had some gang bangin ass people in the house, but my best friend in high school protected me (and I him) from some major foolery, and music brought us together. In high school I helped host beat battles at the local venues, created a website to promote local hip hop, and started recording “producer series” across the west coast.

Section.80 was the soundtrack of my senior year and I know that it inspired so many of us. Some of the people I grew up with in Vegas and became close friends with, went on to become producers (presently!) for some of the biggest artists in the world. Music was our fuel, it was everything.

In my twenties I took my passion for art to the streets to protest against state violence and the prison industrial complex, my playlist was dominated by GKMC and later TPAB. At the first protest I brought my younger brother to we circled around the strip with a banner of all of the names of people who were gunned down by the police while blasting “alright”. I say all of this to say, I love music deeply — and Kendrick has deeply shaped part of that for me. Music, for Black folks, is so much more than entertainment; its essence, joy, release, love, ancestry. Music has introduced me to people I’d never thought I’d meet, it’s helped me through depression and illness, it brings people together, it ruins lives (RIP drake), and it exposes vulnerabilities -- this performance was not an exception to that and I'm grateful for that. We need the music.

Thank you for reading. Part II incoming soon, health permitting! If you enjoyed this please subscribe to a membership or contribute a one-time donation to help me pay for my medical expenses, thank you!