We don’t need AI for elder care, we need a revolution

Introduction

Back in graduate school I was assigned my first year internship at a nonprofit agency in Los Angeles that worked with older (age 55+) and disabled adults (age 18+). Of course as many social work students know, your first year placement is often what you mark as your most “feared” or anxiety-provoking placement on the first year questionnaire. What were my biggest fears? Death and suffering, particularly of older adults. After spending my childhood in nursing homes for my grandpa, I was so scared of being unable to help others like him. Unironically, this was my exact first internship placement as a social work student, and it shaped my thinking around social work forever. I could say more about this, but my primary intent of explaining here is to give a bit of context. I will not be going into all of the details about what casework is, however, casework is an art and practice and should be considered as such by those who hold the jobs and those who receive caseworker assistance. This is one of the first things I learned in school, and one of the few things I found to be very useful. Never feel bad for calling out unethical practices from your caseworker, particularly if they have credentials.

If you’ve never had a caseworker assist with elder care, typically it goes as follows. We receive a referral from family, friends, nurses, doctors, police, or other facilities. We then read through the referral and call the appropriate person to do an intake. Once we deem the case as appropriate for the casework department, we open the case. Sometimes there is elder abuse involved and we are expected to work with Adult Protective Services (APS), ombudsman, the police, and/or mental health. After a case is opened we visit the persons home to do a full assessment. This requires filling out written assessments and informed consent forms in addition to a full evaluation of the home (checking refrigerators, checking rooms, checking outdoors). At my organization our assessment was influenced by the “biopsychosocial” framework and was about 30 pages long. Assessments could take hours and required multiple visits. Assessments and notes, are caseworkers main tools. We are taught that they are intended to help identify different strengths and needs for support for each individual. Depending on the caseworker, each assessment would culminate in a variety of referrals to different services, crisis intervention for those experiencing suicidal ideation, and sometimes reports to Adult Protective Services for “self neglect”. This part really shocked me.

Mandatory Reporting in Adult Care

I came into my social work program with the intent to study the systems responsible for investigating child maltreatment allegations, so I was privy to the process of reporting for children. However, I did not imagine that it would be replicated and weaponized to be used against disabled adults and elders. Thankfully most of my colleagues were against this form of reporting, but there was one colleague who continuously reported people to APS for self-neglect.

In California APS workers are

“… charged with protecting clients’ civil liberties and autonomy. This includes respecting their right to make decisions for themselves even when those decisions jeopardize their health or safety. Exceptions to this rule include situations in which older people lack decision-making capacity to give or withhold consent as a result of cognitive impairments. APS workers are increasingly becoming involved in holding perpetrators accountable by working with law enforcement."

(For more visit the CDSS).

APS workers investigate a variety of allegations including reports of self-neglect which is described as: “Failure to provide food, clothing, shelter, or health care for oneself” — as if this country provides these things freely. I found this to be egregious. While working I heard self-neglect be referred to generally as a term to describe a vulnerable adult living in a way that puts his or her health, safety, or well-being at risk. When I first began my internship I shadowed the colleague who would frequently report individuals for self-neglect. It was because of him that I was introduced to the scope of it. He once reported someone for being unable to change their diapers, due to being unable to afford a caregiver. Another person was reported for smoking marijuana while being on oxygen. Yet another was reported for giving his money to his daughter instead of paying his own bills. His daughter was also reported for financial abuse.

I would say this is atypical, but it’s not. A large portion of casework relies on individuals allowing workers into their homes, often unsolicited, so that the caseworker can verify whether or not they’re providing adequate care for themselves and their families. All of this is shaped by subjective and hegemonic standards. It relies on our own perceptions about what neglect looks like, which differs drastically from caseworker to caseworker. It also requires caseworkers to adhere to an individualistic view of health and wellbeing.

Witnessing this deepened my questioning about the role of social work as a profession in my very early days of starting my degree, and I’m grateful it did. It helped me to realize that in addition to the criminalizing and pathologizing models of “care” that are rampant in social work, we are also agents of the state and thus foundational to state abandonment and state violence. Any caseworker can tell you that we often close cases without making a dent in alleviating the suffering that is caused by the larger issues at the root of “neglect” including extractive and organized abandonment which leads to houselessness, poverty, substance use, and depression. (See Health Communism for more). AI will not fix what is caused by organized abandonment. Neither will these forms of casework. And we must continue to question whether or not the profession of social work can either.

Reporting to APS is antithetical to the preservation of autonomy

As the quote says above, APS is described as protecting right to autonomy, with several “exceptions”. These exceptions are in direct opposition to the protection of individual rights. Autonomy is and requires the ability for people to make their own decisions about the care they receive, and the ability to define what they need support with. So often social workers force their way in and give prescriptive help, help that is frequently not asked for and that is yet still woefully inadequate. In my work I have seen this happen over and over again. It is not simply a pattern of poor decision-making on behalf of caseworkers, but more so a flaw in the entire set up of care via casework. Care via casework is foundationally connected to carcerality and criminalization. I have seen caseworkers force cleaning crews into peoples homes, coerce them into spending down all of their money to fit into federal guidelines of poverty, and have seen a caseworker call APS due to their resistance to his visitations. Caseworkers have an incredible amount of power over patients and clients, and this is bolstered by legal mandates and pressure from supervisors and administrations to oblige. Mandatory reporting is not neutral has several helpful resources about this. They define mandatory reporting as:

" a term used to describe a combination of policies, practices and state-based laws that require certain people to report specific harms to government agencies such as Child Protective Services (CPS), Department of Children and Family (DCF), Adult Protective Services (APS) and/or the police."

Many folks are unaware just how far and wide these laws and regulations reach, and how often they fail to help.

Reporting to APS did not result in additional support

Government agencies describe the upside of reporting to APS in a way that makes new workers believe they will be connecting people to more services. From my experience, this is completely untrue. When caseworkers make reports to APS or receive reports from APS, it often includes various reasons like not enough food and water, homes that need repairs, the smell of feces and urine, symptoms of dehydration, and lack of interest about self. Often caseworkers recieve little to no help from APS or law enforcement in connecting people to these supports, or addressing these issues. That’s because they’re not meant to. In fact, APS would end up re-referring people back to us for services. We had limited options, and so this resulted in a cycle of reporting-investigating for multiple of our clients, and little support. Social work models of care normalize these types of band-aid responses.

We need better frameworks for care, not more chatbots

I believe it is essential that we reframe how we think about care. Current models of casework (capitalistic-carceral casework) require investigation, reporting, and referring processes that do not get at the root of the issues people face. They’re instead meant to delay, distract, and disregard these structural and systemic issues of organized and extractive abandonment. Caseworkers are unable to sufficiently address systemic issues through this normative casework model because they aren’t necessarily meant to address them. As described by Alder-Bolton & Vierkant,

"The care economy—comprising health services, elderly care, disability care, and social work—relies heavily on low-wage, often precarious labor, much of which is performed by workers who are themselves drawn from the surplus class, including women, migrants, disabled people, and racialized communities. These workers are frequently underpaid and marginalized, reflecting their surplus status in the broader economy, yet they are essential to not only the functioning of the care sector but to the maintenance of the labor force and therefore the functioning of capitalism itself."

Casework under capitalism requires keeping people in this ubiquitous cycle of suffering, it’s profitable.

And though agencies may say they have the best interests of individuals in mind, it is not possible to effectively adhere to this model of casework while respecting peoples autonomy. I can tell you that many folks I worked with did not want our help because of the gross violation of their rights. They had few other options. Or at least that’s what they’re (and we are) told.

Chatbots and Predictive Analytics aren’t the answer

To make matters worse, we are seeing more and more efforts to transform already deeply flawed processes and approaches to care into automated ones. In 2020 researchers suggested the use of predictive analytics to better ration limited resources and target “hotspot” communities in need — the typical rational for social service use of algorithms. They defined predictive analytics as a “branch of advanced analytics” that “uses many techniques from data mining, statistics, modeling, machine learning, and artificial intelligence to analyze current data to make predictions about the future”. As many may know, we already see the use of these risk assessment tools in the criminal legal and “child welfare” systems. I will not be going into detail about what these various tools have in common aside from saying that they generally arise from certain ideological frameworks and that these ideologies allow for the perpetuation of capitalism and the carceral ecosystem. (See algorithmic ecology for more).

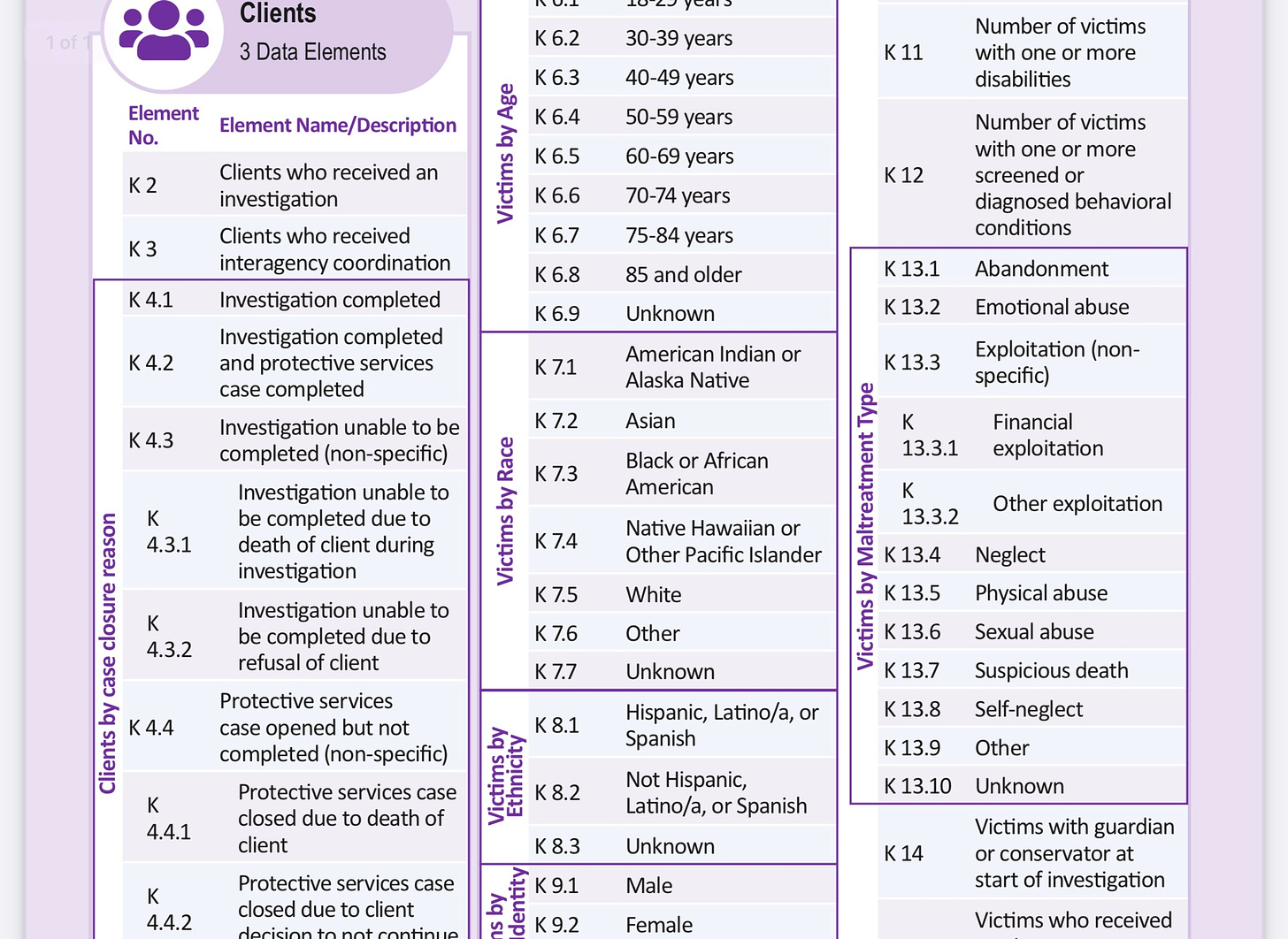

The researchers who presented on this topic in 2020 suggested that the risk assessment tool(s) would use data from the National Adult Maltreatment Reporting System (NAMRS) which is operated by the Administration for Community Living (ACL) and the Adult Protective Services Technical Assistance Resource Center (APS TARC. Information in the NAMRS is supplied from none other than the APS workers discussed above, who collect and input data that includes details of a persons case, educational history, ethnicity, age, gender, location, benefits history, disabilities, previous APS report history, and more. Although many caseworkers are unaware of what happens to the data they collect, it’s important to know the role they play in upholding these systems.

The researchers also stated in their presentation that data may also come from American Community Survey (ACS), Area Health Resource Files (AHRF), County Health Rankings (CHR), Consumer Complaint Databases (CCD), IRS 990, and the USDA Food Environment Atlas (USDA).

Chatbots

Other researchers are marketing other forms of AI, such as chatbots, as valuable and essentially supportive. Rather than highlighting the need for more funding directed at sustaining life, care, and caregiving systems, they tout AI as a way to combat things like loneliness and social isolation. In “ChatGPT: A Promising Tool to Combat Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment” two researchers describe a daily assistant they asked ChatGPT for called LifeGuide. According to them LifeGuide

"leverages its advanced natural language processing capabilities to design personalized and interactive assistance, helping users maintain their independence and improve their overall quality of life. The assistant, named LifeGuide, provides support to users with various daily tasks and activities. Overall, LifeGuide represents an innovative application of AI technology in supporting daily living. By offering personalized, interactive, and accessible assistance, ChatGPT can play a crucial role in helping older adults with MCI maintain their independence and improve their overall quality of life."

They also add that ChatGPT is

"… designed to actively listen, validate, and empathize with the user’s emotions, offering appropriate support, encouragement, and coping strategies. By offering empathetic, personalized, and accessible conversations, ChatGPT has the potential to support the well-being of older adults with MCI, fostering a greater sense of connection and resilience in the face of cognitive challenges"

Reading these specific narratives about the “possibilities” of AI would be laughable if it were not incredibly frustrating and removed from my real world experience as a severely disabled person, social worker, and past care provider. The people I saw when I was a caseworker needed and wanted more human support. They wanted someone to sit with them and talk to them about losing their memories, they needed someone to cut their potato’s because they forgot how to and lacked stable support networks needed to make dinner. People needed help organizing against their landlords who were trying to kick them out of their rent controlled apartments (that they’ve lived in for over thirty years). People did not and do not need a chatbot, they need extensive peer networks to talk to, accessible and affordable housing, and accessible and available nursing and doctor care. And caseworkers don’t need risk assessment tools to help elders and disabled adults. What we need is more funding for community resources so that we can successfully connect people to the supports they need rather than rationing limited services based on these scarcity economics. And families? Families need money to care for their family members, someone to talk to them about end of life planning, someone to help them when they need respite care.

Do not be fooled by researchers that continue to try and invent new technologies like sensors that track human movement and monitor “unusual behaviors” that “may indicate a health issue or distress” without addressing the fundamental issues surrounding care. We should also not be supporting the creation of technological or data driven tools that reproduce, exacerbate, or otherwise lead to institutionalization and surveillance. Many of my past clients expressed being ready to die without actually expressing suicidal ideation. Would technologies even be able to detect nuance? Should they even be able to? At the end of the day people need people, we need each other. And that is OKAY. But we will not get to the world we want without problematizing both AI and the underlying structures and ideologies that currently run the care economy. We have to demand and resist. Strike. Refuse. Now is the time to be critical of everything while imaging and implementing different. But it’s up to us to not accept the status quo, the tech hype, or the norms. It’s time to actually be about revolution.